How to Make Life Less Work-Centric

FINALE: Or, how we can rework this whole economy thing.

America is the most inflexible and decadent of modern nations. The obvious dilemma, here, is whether we will retain any of the lessons from these present calamities or instead try to pretend none of this ever happened. As long as our doddering, atavistic politics remain righteously constipated, the obviousness of our problems will have no effect on our ability to solve them. Immediately before a summerlong cycle of protests against state violence and retaliatory state violence, George Packer argued in an Atlantic essay that America was a failed state. It’s not a thesis I intend to dispute. The forces of money and power would certainly like for this pandemic to smoothly transition to a long orgiastic summer reunion before resuming a previous “normal.” Maybe we will. Habits have a leaden inertia. Insights often relapse into amnesiac complacency.

But crises have a tendency of shaking up the status quo. Americans have had a year of restless and wistful quarantining to contemplate the continuities of swirling rhythms and tendencies that cascade toward daily routines. It is apparent that some of the basic American axioms—hard work is virtuous, productivity is an end—are, if you’ll pardon the Marxist jargon, utter dogshit.

These past several months have been hailed as “The Summer of Quitting Your Job.” About five of every 100 workers in hotels, restaurants, bars, and retailers quit in May. More than 700,000 “professional and business services” employees bailed from their current place of work. More people have left their gigs than any other month that’s been tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. It turns out service personnel are ungrateful to get paid poverty wages by employers who have demonstrated a callous indifference to their general well-being. Apparently, white-collar professionals don’t want to return to wasting their lives on unnecessary commutes, to the dress codes and high-school politics of the office. Across all sectors and occupations, four in 10 employees now say they’ve considered jumping ship from their current jobs and even an overall career change.

Months after Amazon workers in Bessemer, Alabama were defeated in their unionizing effort, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, one of America’s biggest unions, voted to prioritize “building worker power at Amazon and helping those workers achieve a union contract.” As of July 5, two new laws took place in New York City, banning “at-will” employment—under which workers can be fired for any reason—for the fast-food industry. A handful of disgruntled Burger King employees in Lincoln, Nebraska quit and posted, “We all quit. Sorry for the inconvenience,” on their franchise’s sign after repeated frustrations with their restaurant’s management style, understaffing issues, and a “scorching-hot kitchen that at one point allegedly hospitalized a worker with dehydration.” Hundreds of workers at a Frito-Lay production plant in Topeka, Kansas are striking for the first time. And the New York Times reports: “Up and down the wage scale, companies are becoming more willing to pay a little more, to train workers, to take chances on people without traditional qualifications, and to show greater flexibility in where and how people work.”

Maybe this period of seeming dormancy has actually triggered a phase of metamorphosis. Though, before caterpillars become butterflies, they first digest themselves and dissolve into undifferentiated mush.

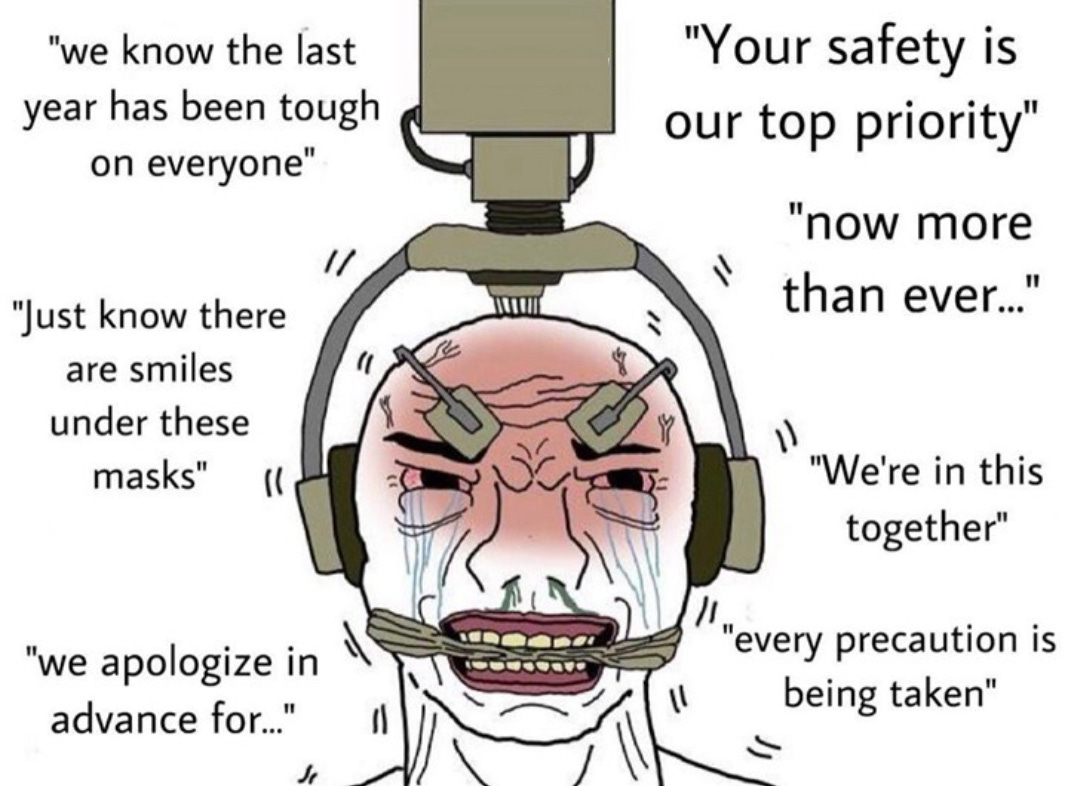

Any radical restructuring of our working lives will face stiff resistance from wealthy business owners and the bloodless flacks who protect their interests. Cultural norms carry an inherent hesitancy that tends to conceive of changes only trending for the worse; this will have to be overcome to bring about a meaningful shift in our attitude towards work. Conservative movement lifers are in the costume business. Their job is to dress up the wealthy’s atavistic avarice and self-serving fatuity with enough cosmetic heft for it to pass as a coherent political program. “Any man demanding the forty-hour week should be ashamed to claim citizenship in this great country,” the chairman of the board of the Philadelphia Gear Works wrote shortly after Ford Motor Company rolled out its 40-hour workweek. “The men of our country are becoming a race of softies and mollycoddles.” The gilded rhetoric of conservative arguments passes into the soft and clammy hands of successive generations, defined by vague gripes and abstracted grievances against even modest reforms.

Albert Hirschman summarizes these kinds of hairsplitting quibbles as appeals to perversity, futility, or jeopardy:

This reform is perverse because it violates the natural moral order.

This reform is futile because it won’t fix the problem it’s meant to fix.

This reform will put everything in jeopardy because it will hurt the very people you’re trying to help.

There isn’t really a convincing argument that things can’t or shouldn’t change. These attempts to rationalize the status quo have been revealed to be debased and overdetermined and underwrought in the same ways that Trump’s syntactically erratic tweets and weird sneering drawls have revealed conservatism to be as cruel and petulant as it appears to be. The dialogue trees have veered psychedelically off-script into some truly bizarre stubbornness that no one can quite place or parse. There is only bluster and a desperate cynicism left. “We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings,” as Ursula Le Guin put it. “Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings.” Once something is done, it becomes possible, and scare stories about the world falling apart become less effective.

Reducing the 40-hour workweek will be dismissed as catastrophically detrimental to business, in the same manner as raising the minimum wage, or implementing the weekend, or any sort of labor law or regulation has been. There is nothing natural about a world in which people spend the majority of their time plopped in front of a desk, or performing gig economy errands, or wasting away at warehouses and factories. There is nothing natural about a world in which people suffer because they work too little or too much.

There is nothing sacred about a five-day, 40-hour workweek. For most of the 19th century, the typical American worker was a male farmer who worked as many as 60 to 70 hours per week, and someone from the household made clothes, furniture, bedding, bread, beer, and even music for the family. Then, the Industrial Revolution alienated people from the products of their labor and thrust consumerism, and the overwork required to maintain it, into hyperdrive. The products generated in factories or the crops produced by farms came from working harder and adopting new technologies and techniques, and the increased output was soon gobbled up by populations that quickly bloated to unsustainable numbers.

Robert Chernomas and Ian Hudson describe Gilded Age working conditions in To Live and Die in America:

“According to a report published in 1893 for the Senate Committe of Finance, average weekly hours in [American] manufacturing in 1850 were a backbreaking 69 hours.

In the steel industry in the United States during this period, men worked twelve hours a day, seven days a week. Transit workers labored seven days a week, 14 hours a day. It was not uncommon for girls working in the laundry industry to work 16, 18, or even 20 hours a day amidst poor ventilation, heat and dampness.

At the legendary Homestead mill owned by Andrew Carnegie, workers put in a twelve-hour day every single day of the year except Christmas and, in a nod to patriotism, July 4. The only alteration of this routine was a swing shift every other week, where employees worked 24 hours straight.”

These grueling schedules and working conditions led many people to die prematurely of exhaustion and disease. This was the product of unregulated market competition, with each factory owner or industry titan wringing every last penny out of their bedraggled workers. The precipitous decline in working hours was made possible by the advent of the internal combustion engine, electrification, and other advances that increased productivity, but successful labor organizing and the Progressive Movement made the weekend and the eight-hour workday possible.

The earliest noted example of a five-day workweek came from a mill in New England in 1908, and it was popularized by the Ford Motor Company in 1926, but it took an economic meltdown to cement the five-day workweek as the national standard. During the Great Depression, reducing hours was considered a way to spread the finite amount of work available among more people. When Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act, it mandated higher overtime pay beyond 40 hours in certain industries, effectively formalizing the five-day workweek.

Across Europe, left-leaning politicians and unions are now advocating for a four-day workweek. In Germany, the nation’s metalworkers union, which has already had success in reducing hours for industrial workers, is spearheading the proposal. In 1975, Germans and Americans averaged the same number of annual working hours. Now, Germany’s GDP per capita is on par with many other wealthy countries, yet Germans work roughly 400 fewer hours per year than Americans. Even reducing work levels to that of Norway and Denmark would amount to giving U.S. workers an additional two months of vacation each year.

Iceland recently implemented the four-day workweek for a select cohort of public sector workers and reported, “Productivity remained the same or improved in the majority of workplaces.” Companies like Microsoft Japan, Shake Shack, Buffer, Unilever, KPMG, and Perpetual Guardian have experimented with the four-day workweek prior to the pandemic, and the idea has been endorsed by former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Arden, and Finland prime minister Sanna Marin. Spain’s government is launching a three-year trial of the four-day workweek, agreeing to cover the costs of companies who agree to participate. Unito, a Montreal-based workflow management company, is allowing workers to choose whether they want to work on weekends or weekdays, in addition to giving them a four-day week.

An article ran in Business Insider last summer as a concern troll refutation of a shortened workweek. The author declared “it would never work in the U.S.” because “low-wage hourly workers, as well as nurses and teachers, would not immediately benefit from these changes.” Of course, for a four-day workweek to be implemented equitably, it would have to be more tactful than whimsically lopping a day off of current schedules. The policy would have to guarantee hourly and salaried employees the same pay for reduced hours and offer more predictable time off. Since median wages are so low, it tracks that many lower-wage workers want higher pay, or feel pressured to want more hours. Roughly half of the workers surveyed in a 2014 poll by HuffPost and YouGov said they would work another day a week for 20% more pay. Part-time workers and those who earned less than a $40,000 salary were more likely to opt into this exchange.

Solving this dilemma, then, would begin with raising the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour, and tying it to fluctuations in inflation, cost-of-living, and productivity. Then, the minimum wage will automatically reset every few years to accommodate itself to the economic conditions of that present without being held hostage by partisan bickering. Though, if American workers were feeling extra saucy, they would argue if the minimum wage kept up with productivity, today, it would be close to $25 an hour. If America had a more competent system of taxation and wealth redistribution, this productivity growth could translate to less time spent working. Today, the top 1% of earners haul in about 10 percentage points more of Americans’ total annual income than they did in 1980. Doling out that surplus wealth among the bottom 90% of earners would give their income a 20% increase—or they could work 20% fewer hours, which equates to giving them a four-day week.

According to The Atlantic, about 70% of American offices are open plan, meaning companies were forced to allow more work-from-home and rethink office meetings and email policy to follow social-distancing guidelines. The current 9-to-5 in-office schedule isn’t even in sync with human productivity peaks (the brain is at its creative apex until 1 PM and reaches maximum physical performance from 5-6 PM). And a recent report by the World Health Organization and International Labour Organization found that overwork is killing hundreds of thousands of people a year. Being in the office for more than eight hours a day is associated with a higher risk of developing stress-related diseases and cardiovascular disorders, as well as inducing fatigue, stress, or headaches.

Unlimited vacation is a common startup perk. Developing a more flexible leave policy could allow for the “remote work movement” to become the norm. Deloitte Australia dumped the 9-to-5 schedule and is allowing their employees to set their own schedules. Businesses like Education Week, Spoken Layer, and Medical Teams International have embraced family-centric schedules that adapt to an individual’s specific needs as they navigate parenthood. Google announced last July that its roughly 200,000 employees would continue to work from home for at least a year. Mark Zuckerberg has said he expects half of Facebook’s workforce to be remote within the decade. Twitter granted its employees permanent work-from-home. And for the past year, WeWork has been advising industry-leading companies worldwide to adapt their workplaces to accommodate rotating teams or expanding to multiple offices in the same building.

While genuine flexibility and remote work can counteract some of the natural hierarchies of in-office work, organizations will have to be wary of how these policies can also create new ones. “My fear is the biggest cost, in the long run, is all the single men come in five days a week, and college-educated women with a 6-year-old and an 8-year-old come in two days a week,” said Nicolas Bloom in an interview with Bloomberg. “Years down the road, there’s a huge difference in promotion rates and you have a diversity crisis.”

The “hybrid” work environment will force companies to strike a difficult balance between two cultures—the heres and theres. If implemented on a mass scale, hybrid work will require reimagining why we even go to the office. There will have to be a concerted effort to not alienate those based on their work preferences, and corporate leadership will have to establish a company culture where visiting the physical office is seen as strictly optimal and pragmatic, done for a specific reason and for a specific amount of time. Companies will have to diversify their managerial teams to mirror the working population—in both demographics and whether they are in-person or remote. Companies will also have to instill purposeful retraining on how to measure work outcomes or how to spot implicit biases. Finally, companies will have to implement clear behavioral guardrails to prevent employees from feeling compelled to make themselves available around the clock or arrive at the office all day, every day.

Despite these challenges, remote work and flexible schedules are worthwhile shifts that will be a net positive for businesses and will overwhelmingly benefit workers. It removes the soft wage theft of commuting and judgment from colleagues for darting from the office at 5 PM. It removes geographic restraints so workers can live in less expensive locations and companies have an expanded recruitment and talent pool. It saves companies overhead by reducing office size and rents. It forces managers to focus on actual project accomplishments instead of the appearance of busyness.

Perhaps, most saliently, if we are to shape and shift a renewed work paradigm, we will need to reconsider the purpose of a corporation. When you peel back the mystic aspirational dada of libertarians, a corporation is nothing more than a legal entity constituted by the government, and its statute defines the parameters of its rights and responsibilities. The concept of “a CEO has a fiduciary duty to maximize shareholder value” exists because a legal construct contains this requirement, not because there is some deistic, metaphysical entity called The Corporation.

The extremities of U.S. free-market thinking would posit that CEOs should have unfettered ability to do whatever they want with little to no regard for human well-being and the livability of this planet, and everyone should dutifully accept it without complaint or recourse. (And, of course, any further government regulation that would impede or curtail the profit motive is no different than Literal Stalinist Totalitarianism.) But if the government already defines what a corporation is, then the government can redefine it. This would not only fundamentally reshape the relationship between labor and capital, but it would also make work more tolerable, rewarding, and offer employees a personal stake in their labor and organizational success.

The German co-determination scheme is a useful template to expand upon:

Corporations with over $1 billion in annual revenue must be federally chartered in addition to their state charters, and a provision that revokes the charter of companies that commit repeated/egregious illegalities.

Company directors must consider the interests of all stakeholders: Employees, customers, shareholders, and surrounding communities.

The boards of directors must be evenly split with a body of labor representatives elected by employees.

Restrictions on stock buybacks, so directors are not incentivized to seek short-term benefits for themselves at the expense of the company.

A supermajority of shareholders must approve political activities, and certain workplace conditions and company policies.

All employees should own some percentage of equity in the company they work for. If the company is publicly traded, all workers should own some percentage of company stock as part of their compensation.

Mandated overtime pay and strengthened sectoral bargaining.

Tax breaks or credits for companies that operate as worker co-ops.

Laws mandating that CEO pay cannot exceed a certain percentage above either the company’s median or lowest-paid worker.

Establish “just cause” rules for firings: Before termination, employers are required to demonstrate to workers that they have engaged in misconduct.

Americans will also have to reconsider its relationship to the market, and accept that four decades of neoliberalism have failed to provide universal access to healthcare, education, quality infrastructure, sustainable energy, housing, or a decent retirement. “Freedom requires keeping us from the markets,” writes Mike Konczal in Freedom From the Market. “That the market can’t provide genuine security against poverty, sickness, old age and disability is something that is understood but not readily accepted, as we keep looking to the market and local communities to solve it.”

Untethering health insurance from work and replacing it with Medicare-for-All would raise wages and enable greater mobility in the labor force (and maybe a boom in entrepreneurship), as people can leave their jobs or start their own business without losing their access to healthcare. It would also reduce costs for businesses—especially small businesses. Passing the Green New Deal would create a more sustainable power grid, which could enable businesses to operate for longer hours at a reduced carbon footprint, meaning they can expand customer service, increase revenue, and create more jobs while reducing the time of each shift. The Toyota repair center in Gothenburg, Sweden, and various Finnish municipal government centers already place people on six-hour shifts while staying open 12 hours a day.

America’s holistic, all-consuming burnout has become our quotidian reality, but it’s something we can fix collectively once we let go of the fantasy of deploying individual hacks to solve social problems. Instagram has a smattering of confessional posts, humanizing offerings like: Look y’all, today was a hard day, I’m blessed by this life but it’s not as glamorous as it seems. Just gotta keep smiling… before concluding with … and I’m still getting up and doing it every day, so why aren’t you? These people are either lying to you, lying to themselves, or both. You don’t fix burnout by going on vacation. You don’t fix burnout through “life hacks,” or inbox zero, or by using a meditation app, or “anxiety baking,” or a Peloton class, or with an adult coloring book. You don’t fix burnout by reading a book on how to “unfu*k yourself.” You can’t optimize burnout to make it end faster.

The best way to treat burnout is to first acknowledge it for what it is—not a passing ailment, but a chronic disease—and to understand its roots and parameters. For many of us, we lack the language and framework to identify and analyze our macro-ailments, and without being able to name and confront burnout, we can never fundamentally change what causes it. In their book, Laziness Does Not Exist, psychologist Devon Price focuses on “the laziness lie” and its three central tenets: Our worth is our productivity, we cannot trust our own feelings and limits, and there is always more we could be doing. We internalize this logic to such a degree that we learn to believe that “our skills and talents don’t really belong to us; they exist to be used. If we don’t gladly give our time, our talents, and even our lives to others, we aren’t heroic or good.” The problem with capitalist ideology, and the self-help nonsense that perpetuates it, is that it insists our very human desire to live for something other than work is simply a challenge to be overcome, feelings to push toward producing, earning, and working more.

I recently came across a rectangular print on Amazon that contains black text on a white background. “WEEKLY SCHEDULE” is written across the top, followed by “Rise and Grind 24/7,” then “New week, new goals!” and below that, HUSTLE written next to each day of the week. Then, at the bottom, is a line of fine print: “You can’t have a million-dollar dream with a minimum wage work ethic.” Well, in China, there’s a growing trend amongst exhausted and alienated students and white-collar workers called the “lying flat” movement, where its adherents quit their jobs and live as minimally as possible. Maybe we’d do better for ourselves if we gave up some luxury to no longer live a life of feigned optimism in pursuit of elusive success. But pulling the world out of this grim, fatalistic slide requires something more subversive than abandoning their dreams; we will need to pursue new ones, radically redefined.

I am often called a pessimist for pointing out the needless and perpetual mass suffering that unfettered capitalism inflicts on the world. My response to these accusers includes two direct questions: What is the social goal we’re working towards? Where is this great hope that is so undeniable and transcendent, one would have to be a true apathetic piece of shit to not recognize? But as the adage goes, a pessimist is just a disappointed idealist.

Believing in neoliberalism as the true end of history is far more bleak and nihilistic than anything I could ever articulate. If we have reached the end of history, then there can be no future. There can be no hope, no change, no alternative, no progress, nothing else to believe in. We can do better, but it requires a recognition that our conception of work, this economic order, and our valorization of rugged individualism is failing and has rendered large swaths of the global population into a chaotic rat race of joyless puppets. During the pandemic, the world added a record 118 million people who are chronically hungry while global billionaires stacked a record $4 trillion atop their already gargantuan wealth. The cost of ending world hunger is $330 billion, which is what these billionaires collectively made in a month. Instead, naturally, we’re privileged to the spectacle of a privatized space race.

Reorienting our conception of work and standards of living would begin with an understanding that the economy exists to serve human needs, and that human needs exist beyond the purview of wealth accumulation and mindless consumerism—and especially beyond the wild, vicious, all-canceling selfishness of America’s plutocrats. We will need to start dealing in the universal “us,” to demand bigger things and a different track in notably more strident and maximal tones, to arrest and reverse a hypercapitalist drift that feels increasingly untenable. The last and great hope is that a present that poorly serves so many cannot possibly be the future.

Maybe this series of howl-at-the-moon rants was both insane and idealistic. But adjusting ourselves to a flailing status quo strikes me as a species-wide death march into oblivion. Regardless, this is all something to consider the next time it’s 4:45 PM and you’re responding to an email from your manager with something like, “Of course! I’m happy to jump in on this project. I don’t mind staying late.”