I'm approaching my mid-30s. Literally dead.

Or what it feels like to be an aging millennial.

I turned 34 last week, and I’m certainly not the first person in my 30s to grow self-conscious of time, but it was a bit arresting to fall asleep to flashbacks to my 20s, sloshing around saucer-eyed in my Hollister flannels and to soundtracks consisting of MGMT and Vampire Weekend. Now I’m wearing nicer flannels and staying in watching HBO with my girlfriend and getting up early for long hikes—or I’m lurking on Instagram, creeping on people I went to high school and college documenting their gentle parenthood journey with their Minimes and matching familial outfits, only to comment “AI slop.” My generation, the millennials, is the last to enjoy an offline childhood and the first to be terminally online. We had all sorts of hyper-filtered vanity and main character syndrome shoved down our gullets. As we approach middle age, with all the decay and fading into the background, we are reacting to this transition by not adjusting to it. Many in my cohort are confronting the end of our youth by performatively embracing youth culture, loudly declaring that the only relevant music is whatever went viral on TikTok, by parroting demure and 6-7, by screeching along to Brat Summer, by spending a monthly mortage on Eras Tour tickets, by gawking at a photo of an 80-year-old man when he was 20 and quipping “twink death is real.” They might genuinely like these things—I’m about those new Wednesday and Geese records—but in a deeper way, they need what these things represent. We are forever trapped in the What Liking David Foster Wallace Says About You discourse.

Millennials dreaded turning 30, conceiving the end of their 20s as The End, so it’s unsurprising that we’re not taking this well. We were doomed to age horribly. Not in a physical sense, since there are always new moisturisers and cosmetic procedures, all kinds of exercise regimens and diet fads released seemingly every month. We’re cursed with the ignominious distinction of becoming the first generation in a while to be less prosperous than our parents, fewer of us are buying homes or having children or pumping up those retirement funds, and any of those hallmarks of moving onto the post-youth stage of life are on an ongoing or permanent delay. If we aren’t building up literal capital, then cultural capital is all there’s left. Along with all the typical young American economic anxieties, there is also the terror that comes with the prospect of not holding the other’s gaze, the smartphone camera as an ontological guarantee of our being. Micro-celebrity, attention, and cultural relevance have become the main sources of meaning.

A few years ago, there was an embarrassing and hilarious piece that ran in the New York Times with the headline, “The 37-Year-Olds Are Afraid of the 23-Year-Olds Who Work for Them.” It opens with this 30-something woman fretting that the emojis she uses are now considered uncool, and this banal insecurity hints at a deeper ambient dread around aging and no longer being the locus of popular culture. But it’s more embarrassing to try and keep up with trends than it is to fall behind. We spent so many years flinging the “fellow kids” meme around, and now we’ve aged into the condition of righteously performing the role of Cool Dad or the hip Wine Mom. Again, it’s normal and healthy to progress your taste in music and movies and books past the stage of when we were teens and to open yourselves up to new releases and burgeoning scenes and music trends and pop culture. It would be embarrassing to turn into the Rolling Stone staff and only begrudingly admit that good music has actually been made since 1975. But I can’t help but look at greying, softening parents parading around in Taylor Swift t-shirts on their TikToks, or posting about how validated they feel because Barack Obama included Charli XCX songs on his year-end playlist, and think that these people like things to be seen liking them.

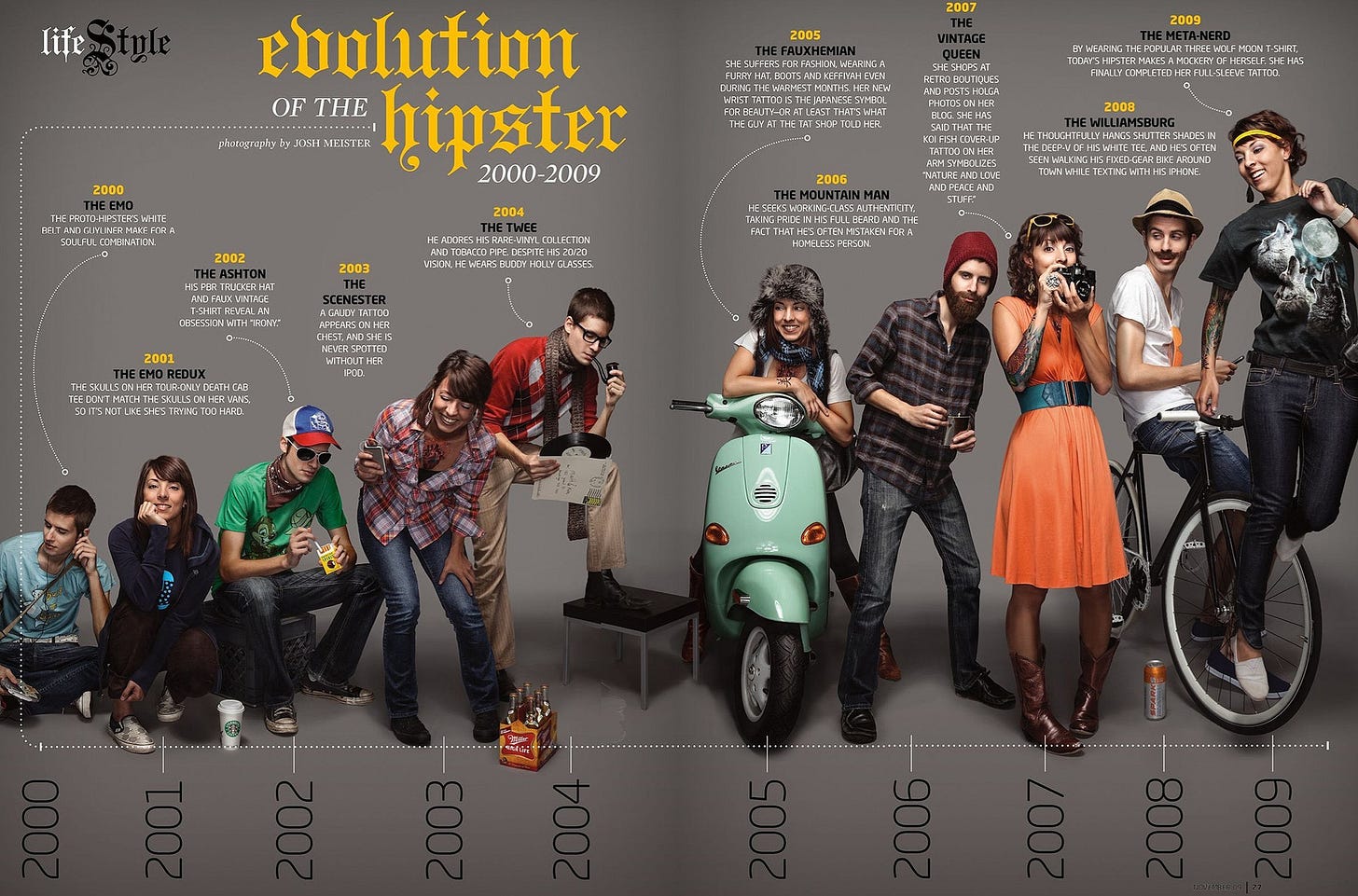

This is all made a little bleaker considering millennials were once defined as the “hipster” generation—prancing around Williamsburg or some similarly offbeat neighborhood, swilling IPAs at backyard parties, jamming out to the latest indie darling. We were once cloyingly countercultural, and now we are obnoxiously chasing the mainstream, which resigns us to the more deflating reality. Maybe we never had any unique aesthetic taste and instead lived our lives terrified of ever appearing not to be The Right Kind of Person, which was only really defined by our consumer patterns and standing within the culture war.

They say what happens online is not real life, but strangely, it does expose what we truly value despite all our professed lofty ideals. This supernova of fast and free-flowing information and practically infinite knowledge to be learned to hone all sorts of skills, but social media has deepened this libidinal urge to be seen for our most superficial qualities. As Naomi Klein has observed in her book Doppelganger, our personhood has been bifurcated into our physical selves and our online selves, and if the chasm between the two splits deeply enough, it can create a crisis of identity. As the physical self ages faster than the online self, the cleft between the two only widens and amplifies this effect. (And not to be conspiratorial about this, but it wouldn’t surprise me if social media as we experience it today is a direct descendant of the innumerable clandestine mind-control experiments that the CIA has been engaging in since WWII, a commodified product borne out of the lessons learned from those experiments to induce a form of Dissociative Identity Disorder in otherwise normal people. But that’s for another post.) Anyways, in this environment, it makes a bleak sort of sense that the teenager is the most aspirational form—no one expects accountability or responsibility from you as you insist that you are the center of the universe.

We have endured two once-in-a-generation economic collapses in the last 20 years, but these hardships have strangely given us an overarching, all-devouring excuse to remain mentally and emotionally stunted, to pursue maximal comfort at all times. Since life is hard, we’re encouraged to do what’s easy rather than what’s right. Friendships and relationships are hard, but Netflix and Instagram are easy—so let’s doomscroll or binge The Office instead of going to a party or joining a club. Good therapy is hard, but a shitty therapist who demands nothing from us is easy—so let’s cycle through therapists until we find one who does nothing but constantly validate our priors. Treating service workers with any baseline level of respect and humanity (for some unfathomable reason) is hard, but using slop delivery apps to avoid them is easy—so we text them to leave the food outside rather than saying hello or making eye contact. Reading a complex novel with intricate symbolism or watching an arthouse movie with deep allegories is hard, but reading YA novels and watching Harry Potter or Marvel dreck for the umpteenth time is easy—so let’s never challenge ourselves with anything that might make us feel uncomfortable. These behaviors are sometimes understandable, but they were once done sparingly and with a tinge of shame. Now, anything that used to be embarrassing has been pathologically excused and rationalized and justified under the banner of trauma or weaponized social justice rhetoric, so garbage behavior or lerned helplessness is now something to be proud of, an inverted pretentiousness. There are subreddits dedicated to grown-ass adults who proudly eat nothing but chicken nuggets and Kraft mac-and-cheese, and “girl dinner” is a meme to describe 30-something women who will eat pickles and popcorn for dinner.

As Sam Kriss notes, all of this was presaged in the show Girls:

The entire show is about [Hannah Horvath] slowly coming to terms with the fact that she does not quite fit in the world, even though it keeps reflecting all her bad qualities back at her. Hannah Horvath is an index of her time’s disjuncture from itself. Selfish, sometimes callous, grasping—but also self-exposing, constantly getting her tits out on screen and her deeply private experiences out in the pages of some exploitative online publication. More immature the more she ages, hanging out with schoolchildren, adopting the sexual persona of a schoolchild. Most of all, there’s her OCD: everything she does has to be repeated, held in stasis; one moment can’t simply progress into the next.

Aging reveals who is actually beautiful. I stopped caring when I hit 30, but I might have a mini-freakout when 40 is imminent. Otherwise, what’s the alternative to not coping with aging? I have friends who spent their 30s pretending they were 22 forever, preceding with an endless series of sloppy hook-ups and late nights getting puke-stains-on-your-shirt drunk, living carefree without a plan or tomorrow—and it always struck me as a circular and deadening existence. So you do what everyone has done to grapple with aging and death over the millennia: Lean into friends, family, and/or children, take care of your body and mind, come up with a career plan, try to chill out and enjoy the small things in life, take up some new hobbies, maybe embrace some kind of spiritual practice. Or you can deal with aging by having worse things in life that torment you.

We are the confluence of all the experiences of our pasts and all those to come in the future. The ride is the fun part. Laugh at it all, try new restaurants, don’t be afraid of acting your age, don’t let maturity force you to take yourself too seriously, and develop some new skills. We’re all scared of what’s around the bend to some degree, but sinking into what we are and reflecting that positivity and acceptance out into the world is all we can do. The existential dread inherent to our insignificance can actually be gestalt-shifted into a boon because it’s a realization that we’re all subject to the same fate, and therefore, we don’t have to obsess over bullshit status or job titles or FOMO or keeping up with goofy trends that everyone will forget about in six months. So spend your time appreciating the miracle of life while you have it. Or we go out like the ending of The Irishman, but we’re crotchety hipsters who find out that all the influencers, podcasters, and life coaches we once followed are all dead.

As someone who is nearly 50, you have my sympathies.

“to induce a form of Dissociative Identity Disorder in otherwise normal people. But that’s for another post.” Yass, this sounds fun!