The Year that was a Long Sunday Scary

PART 4: On mindfulness, meritocracy, and burnout.

It was a grey April afternoon during the nascent stage of the pandemic, and the shelter-in-place mandate terraformed Chicago into something between an omnipresent stillness and a soft apocalypse. From a high enough vantage point, you could see expanses of sidewalk tiles streaking through empty neighborhoods several miles away, giving itself to anomic sprawl. There’s a strange and queasy equilibrium to it, gazing upon an empty city that’s palpably vast and indefinitely stuck in a state of suspension.

Being a deeply inessential worker, I was trapped like a rat in the same apartment day after bleary day, my sense of time utterly busted and borderline nonexistent. The typical business hours were spent slouched on my couch and my MacBook snugly situated on my lap, flicking my fingers through an endless scroll of LinkedIn posts that were somehow both forgettable and relentlessly thirsty. Most of them, at a surface level, are variations of job-hunting advice with a tone of forced positivity. Fittingly, the top story in LinkedIn News that day was “U.S. Jobless Claims Reach 30 million.” These kinds of influencer-peddled career tips could range anywhere from well-intentioned to outright grifty, but it seems to me that people need guaranteed healthcare more than résumé formatting advice.

All the psychic momentum I’d built up to propel myself through an upward linear career trajectory soon guttered out into despondency, my immediate future abruptly truncated. It was typical, almost comically routine, for people to begin an email with “I hope this finds you well,” or ask, “How are you holding up?” and then I’d answer, “Well, you know.” That “you know” encompassed a lot left implied: eroding mental health, throbbing uncertainty, full-bodied atrophy, endless boredom, solitary despair, casual collapse-of-democracy anxiety. Each and every day throughout this pandemic felt as fragmented as it did monotonous. None of it really fit with each other or even identified as having once comprised any part of a coherent whole. It all came from the same shattered “normal,” but each passing moment entirely its own.

Police officers hauling out pallets of hoarded hand sanitizer from a personal storage facility. Donald Trump reading a long list of CEOs’ names in the White House’s rose garden for reasons that remain unclear. Amazon unveiling “Heroes” shirts for its Whole Foods employees before working to slash their “hero” pay. People tearfully pleading to a Fox “News” reporter that Michigan must be re-opened so they can buy lawn-care products or schedule a hairstyling appointment, then a sitting president tweeting “LIBERATE MICHIGAN.” Impossibly obtuse celebrities singing along to John Lennon’s “Imagine” into their phones. A Texas mayor berating citizens for expecting government assistance during a deadly winter-storm-induced statewide power failure, writing in a since-deleted Facebook post, “only the strong will survive and the weak will perish.” And roughly a 9/11’s worth of people dying the same way, of the same virus, every single day.

Being unable to deal with all this critical and compounding societal failure should be a legitimate excuse for failing to answer emails or missing the occasional deadline. This tragicomic shitshow was simply too much to be borne without occasionally crumbling to pieces. Containing the swelling Camusian doubts each workday is a perfectly respectable achievement.

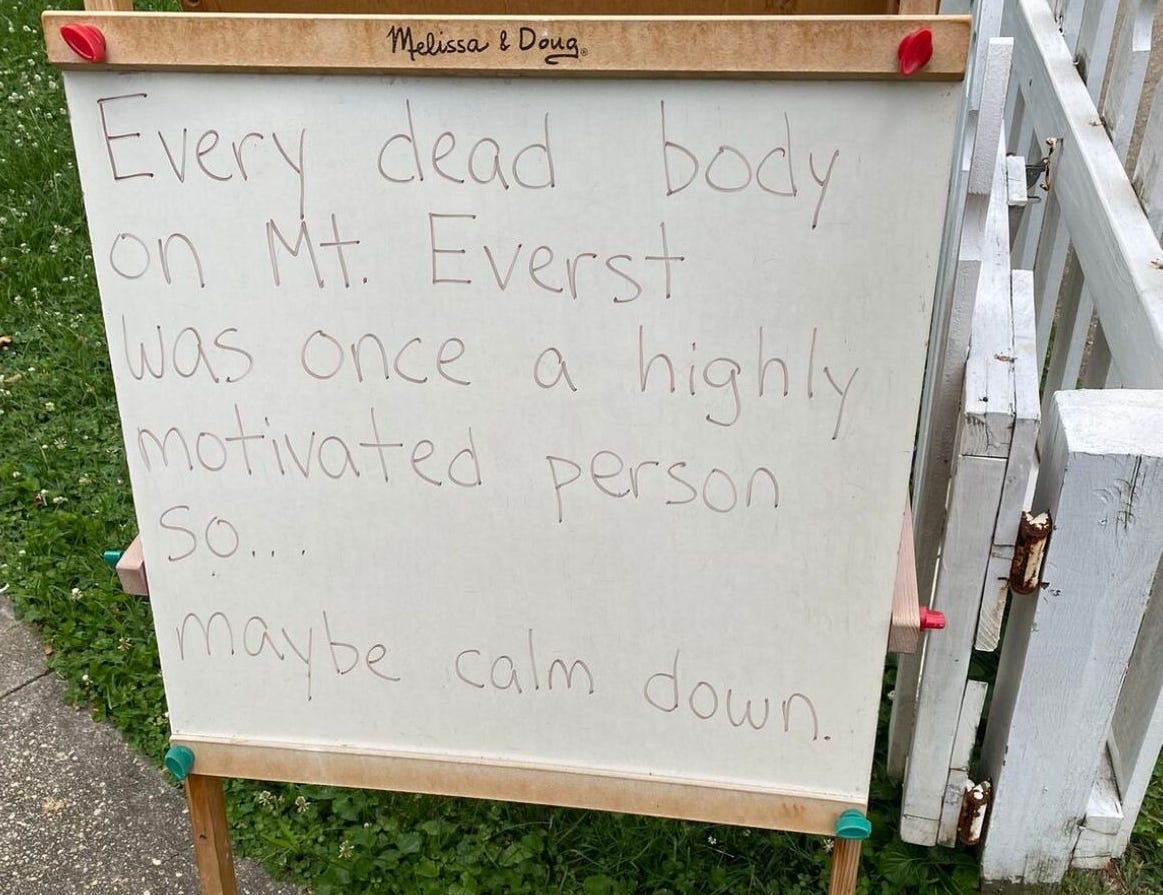

In the 2010 book, On Time, Punctuality, and Discipline in Early Modern Calvinism, scholar Max Engammare argues that the Calvinists replaced the Medieval Catholic conception of time (which was cyclical and based on recurring seasons and holidays) with a linear view of time (which was always running out). This lockdown revealed the neoliberal anxieties that accompany this linear perception. The dread specter of our internal managers loomed, urging us to invest hours upon weeks into something “productive,” honing skills we could advertise on our résumés and boast about in some fanatical post on LinkedIn or the Medium Daily Digest. I’d click on articles like “How I Optimized My Morning Routine To Accomplish All My Daily Tasks Before 9 AM!” only to discover the author does a set of burpees in between sprints of writing thousands of words about how they write thousands of words every day.

Weekends serve as officially sanctioned respites from productivity, but this year was one dragged out Sunday scary. Last spring, I channeled this newfound abundant free time on Stackskills developing a stronger grasp of Adobe Creative Suite until I realized I neither had the attention span nor the spirit required to thwart my own sloth. The sirens of nihilism, solitude, and Netflix binging became harder to ward off. I felt this deprivation like a vitamin deficiency, slowly leeching my will to do much of anything outside of menial chores. The bad conscience inevitably seeped in, the perverted impulse to self-flagellate and embrace this insane cult of action.

As American business became more efficient at turning a profit, the threshold of competition in the human resource market could only be met with a single-minded dedication to thriving in an increasingly vicious economy. We are less so human beings with complex, variegated histories, but potential members of the job market with certain workplace deficiencies, cheerfully indentured to the idea that self-worth isn’t tied to personal integrity, but professional accomplishments.

While the Protestant ethic is a useful framework in analyzing how God fused with profit and careerism in the American psyche, philosopher Slavoj Žižek has argued a popular western Buddhism has supplanted Christianity as a type of “spirituality, self-experience, ideological self-understanding” that integrates perfectly with this new era of global capitalism. This pseudo-spirituality is a bastardization that mimics orthodox Buddhism in form and aesthetic, as a religion based on self-reflection, internal meditation, a radical evolution of subjectivity was distorted to comport with an economic system with an almost social Darwinist tone to it. Capitalism is delicate and renders the individual fragile. A demand for detaching from these woes emerged, a form of negating the self into practical nothingness. This marked an evolution toward inspirational meta like mindfulness and internalized self-help.

These structures and institutions have crowded out the subtext entirely; this spirituality isn’t portrayed as anything close to resembling something revelatory or emancipatory or delivering a heavenly reward. The end goal is something preposterous and glaring. No longer a technique linked to its Buddhist origins, mindfulness is packaged and sold as something to cure burnout, increase happiness, and boost productivity. A search for “mindfulness” on Amazon turns up over 30,000 book results alone. The marketing of mindfulness as a commodity to be sold in a brand culture is, according to the late psychologist Jeremy Safran, “the marketing of a dream; an idealized lifestyle; an identity makeover.”

Subscription-based meditation apps like Headspace, Aura, Breethe, Buddhify, and The Mindfulness App exist in lavishly ornate forms, all promising to help find balance in life through guided meditations and breathing exercises. More than 100 million people have Calm on their smartphone, after downloads surged by a third last spring. For $15 a month, you can stare at towering mountains or serene lakes or listen to Harry Styles’s dusky voice coo over soothing piano music as you lull away to sleep.

Mindfulness training programs have also proliferated in the corporate sector. Clearly, there’s a bottomless hunger among dysfunctional companies to do an organizational makeover into something more compassionate. Google’s “Search Inside Yourself” is a mindfulness-based emotional intelligence training billed as a transformative promise to reduce stress, improve focus, raise peak performance, and improve personal relationships. These programs encourage the idea that the last vestige of control is managing the stresses and anxieties of capitalism in an enlightened way. People shouldn’t question its structures, but rather internalize everything to maintain the same tireless vigor the office grind demands of its constituents each dreary day. None of this was quite on purpose, really, but it doesn’t feel like an accident, either.

These mindfulness seminars are similar to the “human relations” and sensitivity training movements popularized in the 1950s and ‘60s. These programs were largely discredited as fraudulent horseshit because they manipulated counseling techniques like active listening: Employees were made to feel their concerns were heard, only for their considerations to be discounted when it came to actually improving suboptimal workplace conditions. This came to be known as cow psychology; content and docile cows produce more milk, after all.

Mindfully focusing on the present means not thinking about the past or the future. According to historian Russell Jacoby, this popular form of tranquil forgetting produces something called “social amnesia.” Intentional breathing patterns won’t chip away at a $1.6 trillion student loan debt crisis; it won’t stop the endless wars or the CIA death squads; it won’t extinguish the zombie Arctic fires or the rampant wildfires or even the ocean fires; it won’t mitigate the Delta variant; and it certainly won’t prevent proud MBAs from channeling their personality disorders into “management styles.”

“Capitalist realism” is a term Mark Fisher used to describe the phenomenon whereby people are so committed to the inevitability of our current socio-economic arrangement, that it’s rendered an invisible, de facto state of reality without any tangible alternatives. We’ve become so inured to this 40-year neoliberal reign, we forget its structures are all debatable means of organizing a society. Much of the popular imagination has narrowed and flattened to suit the crude and idle whims of various oligarchs, so we’ve tacitly accepted a hypercompetitive job market, the concept of unemployment, the 40-hour workweek, and the existence of billionaires.

The result is a micro-caste of puffy swells comprising a political and media apparatus ideologically captured by the mythic power of rugged individualism, emphasizing personal responsibility above preventative and structural change. These are not exceptionally discerning minds, of course, but even if they remain stuck on describing actions that are so limited in scope in comparison to the sheer mass of annihilating decline, they surely can see all the ways in which the toxic runoff of inequality can be felt. “Capital makes the worker ill, and then multinational pharmaceutical companies sell them drugs to make them better,” Fisher wrote. “The social and political causation of distress is neatly sidestepped at the same time as discontent is individualized and interiorized.”

In mental health reporting, it’s rare to see coverage of how policy failures have led to a spike in suicide rates or loneliness, but there are boundless headlines like: “Mental health during coronavirus: Tips for processing your feelings,” or “Coping With Loneliness During a Pandemic,” or “A guide to taking care of yourself during the pandemic.”

The gaze gravitates toward the magical gumption of the individual, or as Fisher calls “the privatization of stress,” describing it as:

“…part of a project that has aimed at an almost total destruction of the concept of the public—the very thing upon which psychic well-being fundamentally depends. What we urgently need is a new politics of mental health organized around the problem of public space.”

In April, The New York Times published a story titled “There’s a Name for the Blah You’re Feeling,” accompanied by an illustration of a sad-but-not-too-sad-looking person holding a cup of coffee with some oranges strewn around their feet. The piece describes a mental condition known as “languishing,” and the author calls it, “the neglected middle child of mental health … somewhat joyless and aimless.” It suggests blunting this condition with flow, “that elusive state of absorption in a meaningful challenge or a momentary bond, where your sense of time, place and self melts away.” And some ways to spur this euphoric mental space include early-morning word games or a Netflix binge.

All of this is fine and dandy within a parallel universe not battered by various blistering inequalities. But pieces like these are an example of the Forer Effect, in which people fixate upon a reflection of themselves within deliberately vague language, filtered through a neoliberal tint. They’re instructed, convinced that a change in their personal habits or downloading an app can jolt them out of their degenerative ennui. These articles, palliative as they may be, are satisfying like a horoscope—describing our special snowflake selves in a gently patronizing but relatable way that lends an abstract phenomenon a snappy name. The internet has always infatuated itself with quirky and pithy BuzzFeed-like labels: Ravenclaw, woke, neurodivergent, empath, INFP, Virgo. Corporate media satisfies this demand by proffering new phrases to describe increasingly common experiences—pandemic-anxious, pandemic-distracted, pandemic-depressed.

This reflexive and blinkered commitment to “hacks and tricks” as a solution to an economic depression atop a plague atop a mental health epidemic scans as dishonest and cloying. It’s a kind of urbanite, white-collar piousness that’s substantively no different than “thoughts and prayers” as a counter to a concerning uptick in mass shootings.

This type of coverage should be obviously facile and unconvincing. It rarely advocates for systemic reform to reduce the traceable sources of mass distress: unstable and unsatisfying work, the palpable fear of penury, stingy and punitive healthcare, decreasing economic mobility, acute alienation, inadequate leisure time, a valid sense of powerlessness in the face of a corporate-run government that serves plutocrats lavishly and inflicts harm on everyone else. “Mental health and many common mental disorders are shaped to a great extent by the social, economic, and physical environments in which people live,” according to a World Health Organization report on Social Determinants of Mental Health. “Social inequalities are associated with increased risk of many common mental disorders.”

In an episode of the podcast Citations Needed, media critics Nima Shirazi and Adam Johnson observe a suspicious omission from the general pandemic reporting:

“Actionable, proven political solutions to mental health crises that operate under the radical assumption that social problems may require social solutions. Nowhere in any of these articles is the idea that socialized medicine, guaranteed income, free childcare, student debt relief, or rent and mortgage cancellations, may be the best and most rational ‘hacks or tricks’ to actually improving the mental health of people at scale.”

In the bottomed-out weeks of the pandemic, the only murmurs of mental health as a policy issue arrived when Republicans spoke about “deaths of despair,” and the social and mental cost of locking people down. Their solution, of course, was dark and overtly recursive, to shoo people back to work at death traps, which gave rise to those pudding-brained anti-lockdown protests. The Democratic response, which never quite rose to the level of being a counterargument, was a discursive acknowledgment of widespread suffering that flailed in the face of the GOP’s own bulletproof shamelessness. “Millions of people have lost their employer-tied health care over the last two weeks because of the pandemic,” Hillary Clinton tweeted last April. “It’s an easy call: Re-open the health care exchanges.” This kind of concern trolling particularly stings not so much because of how sincerely misplaced it is, but because of its criminal futility.

Self-improvement is a worthwhile solution to individual problems, even if broader American culture treats personal and collective responsibility like mutually exclusive concepts. It’s important to not allow an abusive boss to dictate your sense of self-worth, but it does nothing to ameliorate the power imbalance that permits such a boss to abuse their subordinates—er, “team members.”

Dale Carnegie arguably created the modern American self-help industry with his blockbuster personal advice tract, How to Win Friends and Influence People, which distilled many dubious superpower incantations into, well, befriending and influencing people. Carnegie’s rise also coincided with the emergence of the corporate management class and a culture newly defined by mass consumption and individualism. His biographer, Steven Watts, also credits Carnegie’s massive success to the economic devastation caused by the Great Depression. As Watts recounts, Americans were almost universally humiliated at the sudden onset of poverty—RE: “temporarily embarrassed millionaires”—that followed the stock market crash. People blamed themselves for their suffering more than a lack of banking regulation or reckless speculation, so they opted for the “reinforcement of basic institutions” over “revolutionary agitation.”

Dale Carnegie saved the culture of individualism, as one of his ads stated, “If you have a sincere desire to improve yourself, come along.” Panicked individuals in a middle class plagued with various paranoid obsessions doubled down on preserving a mystical American way of life. Now, much of self-help isn’t help at all: It’s an $11 billion industry whose end goal isn’t to alleviate late-capitalist entropy but to provide further means of self-optimization. The self-help complex doesn’t offer any insightful analysis of a flexible gig economy that doesn’t particularly value anyone’s labor. This isn’t too dissimilar to the way Carnegie’s advice diverted attention away from the causes of the Great Depression. This swelling industry of how-to advice is a matter of feints and sacrifices to help us settle contentedly into a talismanic legerdemain of sorting the deserving from the lazy, the same basic delusion underlying and reinforcing the dominant American concept of fairness.

Meritocracy seems like the ideal system that answers what Tocqueville called the American “passion for equality.” If the opportunities are truly equal, the results will be fair. After all, individuals should be rewarded according to their efforts and natural, God-given talents. A British sociologist named Michael Young coined the term in the late-1950s when he published The Rise of the Meritocracy. This new word was intended to be a portend: In his satirical fantasy, modern societies would develop precise mechanisms to measure children in a way that would stratify schools and jobs, creating a new form of rigid and oppressive inequality. The word lost its original dystopian meaning when, in the decades following World War II, the G.I. Bill, the expansion of standardized tests, the civil rights movement, and the opening of top universities to students of color, women, and children of the working class all combined to offer a wider range of citizens path upward. Of course, American society remained (and still remains) a glaring apartheid in a variety of ways, but it was the closest to equal opportunity this nation had ever witnessed.

After the 1970s, a system intended to give each new generation an equal chance to rise created a new hereditary class structure and has slowly hardened since. Educated professionals passed on their money, ambitions, connections, and work ethic to their children, while less educated families fell further behind. After several decades of meritocracy, Millennials came of age during the 2008 financial crisis, the decline of the middle class, the rise of billionaires, and the steady decay of unions and stable, full-time employment. A generation of over 70 million collectively owns 5% of America’s wealth. This idea of fairness remains vexing and shockingly persistent, accounting for meritocracy’s cruelty. Those who didn’t make the cut have nothing to blame other than their latent laziness, their moral defects, their insufficient grind. Those who carved out a pleasant niche for themselves can feel morally pleased with their talents, discipline, good choices—even a grim satisfaction when they encounter someone “less successful.”

In this context, the idea of Your dream job is out there, so never stop hustling feels like a greasy indulgence that almost nobody grasps, but everybody feels obligated to try forever. Rates of depression and anxiety in the U.S. are “substantially higher” than they were in the 1980s, and 87% of employees report they’re not engaged at work. Meanwhile, we’re told to love our jobs, to find meaning in them, as if work were a family, or a religion, or a body of knowledge. Or, as Laura Empson has observed in the Harvard Business Review, elite white-collar organizations use an up-or-out policy to exacerbate their employee’s insecurities and fears of being “exposed” as inadequate, which creates internal cultures that are self-motivating and self-disciplining:

“…elite professional organizations deliberately set out to identify and recruit “insecure overachievers” — some leading professional organizations explicitly use this terminology, though not in public. Insecure overachievers are exceptionally capable and fiercely ambitious, yet driven by a profound sense of their own inadequacy. This typically stems from childhood, and may result from various factors, such as experience of financial or physical deprivation, or a belief that their parents’ love was contingent upon their behaving and performing well.”

All this mindfulness and self-help and optimization and overwork have culminated in “burnout,” first recognized as a psychological diagnosis in 1974, and is now the dominant American condition. It was applied by psychologist Herbert Freudenberger to cases of “physical or mental collapse caused by overwork or stress.” Essentially, burnout is when someone slams into the wall of exhaustion and continuously rams into that wall hoping to disintegrate it, brick by brick. This process can last for days or weeks or years.

Describing Millennial burnout, specifically, is to acknowledge how a broadly shared generational reality is influenced by the status quo. Americans under 40 are saddled with and crippled by debt, working longer hours for diminished pay and even less job security, operating in precarity, grasping to achieve the same standard of living as previous generations. Efforts poured into networking, personal branding, and child-raising aren’t even legitimized by contemporary economics, at least in terms of counting towards national GDP or warranting some form of compensation. And for having the audacity to vocalize this collective stress, or deign to request worker protections or a stronger safety net, the stock response is a swift and stern browbeating of a supposed unearned sense of entitlement. If we work harder and persist, we’re reminded, meritocracy will prevail. If value was truly tied to competence, most of our politicians and pundits would be folding Oxford shirts at the Gap.

The feeling of accomplishment that follows an exhausting task—admittance into an elite university, earning a coveted degree, securing a glossy internship, logging 80-hour workweeks—tends to feel more inadequate in an increasingly unappeasable and arbitrary and disastrously stratified society. Certain hubristic delusions fade over time. Josh Cohen, a psychoanalyst specializing in burnout, summarizes this dynamic aptly:

“The exhaustion experienced in burnout combines an intense yearning for this state of completion with the tormenting sense that it cannot be attained, that there is always some demand or anxiety or distraction which can’t be silenced. You feel burnout when you’ve exhausted all your internal resources, yet cannot free yourself of the nervous compulsion to go on regardless.”

One of the main causes of burnout is a perceived lack of control, which has increased with remote work, as the already negotiable line between the office and home blurred into something unrecognizable. According to a global study published by Harvard Business Review in February, 89% of employees said their work-life balance had deteriorated since quarantine started, and 85% said their well-being declined, likely due to increasing job demands. Prior to the pandemic, Millennials popularized trends like athleisure or Amazon Fresh because the time they save allows for more work. Over the past year, the cloffice—a closet that doubles as an office—popped up on Pinterest and Instagram, sparking inspiration on makeshift solutions to separate workspace from living space. Someone coined the portmanteau, “coronapreneur,” as a way to channel this shelter-in-place free time, and accompanying slow-rolling trauma, into a positive growth experience. Our new unofficial job title: CEO of Myself.

In a more flattering light, our growing affection for labeling modern experiences like burnout, or finding hacks to solve systemic issues, or speaking candidly about the elusiveness of meritocracy resembles an over-individualized society scrambling to collectively grapple with these pressing issues. We’ve become, as a culture, overinvested in coping mechanisms.

A week after the New York Times ran their popular piece on languishing, they issued a follow-up called “How to Flourish,” which prompted readers to “celebrate small things,” and “do good deeds,” and “find purpose in routines,” and “Sunday dinner gratitude” to maximize their post-pandemic life. It’s a touching—if not a saccharine—sentiment, but perhaps the Times isn’t speaking to the lived experiences of millions toiling away in some degree of precarity and uncertainty. There is something suitably Trumpian, even greasily poetic, about earnest life-hacks and career advice being humped to death by interchangeable grifters cooing brand-gilded lies to gormless rubes.

Over a year later, flush from surviving a particularly dismal winter, the email greeting “I hope this finds you well” has since devolved from a half-sincere opener to an overleveraged punchline. I remain slouched on my couch with my MacBook snugly situated on my lap. Now, I drift through LinkedIn and Medium Daily Digest posts about successfully completing a strategy boot camp or “How I Organized My Office Desk to Maximize Workflow,” all of it cheesy and chiseling in all the ways that every productivity blog serves as a demoralizing annoyance. It feels as if our brains were in low-level fight-or-flight mode at all times, our lives in stasis or hiatus. Our daily task was to dutifully isolate, prioritizing our mental energy for survival while the commanding heights bumbled from one haphazard blunder to the next. And either out of instinct or inertia, our work culture still tips toward productivity.

Somewhat surprisingly, though, the top story in LinkedIn News that day was “A New Way to Sign Off Your Email,” with a recent post by the vice president of Amazon Web Service serving as an aspirational template for intra-office correspondence that dampens the expectation of all-hour responses:

“TRULY HUMAN NOTICE: Getting this email out of normal working hours? We work at a digitally-enabled relentless pace, which can disrupt our ability to sleep enough, eat right, exercise, and spend time with the people that matter most. I am sending you this email at a time that works for me. I only expect you to respond to it when convenient to you.”

This post went viral and was unanimously praised as a thoughtful caveat to an email signature. Accompanying this feel-good discussion in the LinkedIn Top News were stories like “An Almighty WFH Standoff Looms,” and “Why the Workweek Needs a Makeover,” and “Let’s Lose the Idea of a ‘Dream Job’”—almost serving as algorithmic spiritual companions. They all articulated a similar theme: We should work to live, not live to work. Relinquishing the fantasy of finding fulfillment through our jobs, and even logging fewer hours at the office, may help alleviate burnout and establish a sense of self-worth that isn’t linked to our “merit.” At this nation’s typical glacial pace, after 600,000 mostly preventable deaths and a low-key imploding society, even these vague stirrings qualify as progress. It’s not quite guaranteed healthcare, but it’s better than résumé formatting advice.